E11. Lou Reed’s Nephew on Snark

“Snark is the aloof, eye-rolling negation of things typical of people your age. It has lately come under fire from members of my generation who would maybe like to believe in things."

“What is your view of snark,” Lou Reed’s Nephew asked me one evening, just as I was headed out the door.

“I saw Pulp Fiction in a theater,” I said.

“Film Forum?”

“A suburban cineplex, the day it opened.”

Lou Reed’s Nephew sighed. “You must breathe the stuff. I was born too late.”

“For what? The Civil War? The Nuremberg trials?”

“Those, too. But I meant for seeing Pulp Fiction the day it opened in the golden age of snark.”

I wasn’t sure what he was getting at.

“What are you getting at?” I said.

“A war is on,” he explained. “A war between snark and smarm.”

“These are bands, Snark and Smarm?”

“No,” he laughed. “But that’s very nineties of you. Like they were on Matador. No, they are tones. Or styles. Dispositions, perhaps.”

“A war between invisible kingdoms,” I suggested.

“More or less,” he said. “Snark is the aloof, eye-rolling negation of things typical of people your age. It has lately come under fire from members of my generation who would maybe like to believe in things and believe snark is standing in our way.”

“I see.”

“But then, your friends—the snarks—reply that the critics are guilty of smarm, an anti-skeptical flattery of reality.”

“Can you give me an example?”

“LinkedIn.”

“Any particular …”

“All of it. Smarm is earnestness that has known snark, assimilated it, but is plotting a return to sincerity.”

“I’m afraid you are speaking abstractly.”

“Let me try another approach,” he said. “There are three kinds of people.”

“Only three?” I asked.

“Precisely three,” he said, turning to the whiteboard on which he scrawled diagrams intelligible only to himself when hand waving failed. He drew a two-by-two grid and began labeling its rows and columns.

“They can be categorized based on how they feel about other people and how they appear to feel about other people. There are haters, who do not like people and do not hide it. There are fakers, who do not like people but, understanding that this is unattractive, pretend to love them. And then there are the so-called ‘good people’ who seem to love people and act accordingly.”

“You seem suspicious of the ‘good people,’ as you call them.”

“I call them ‘the goods’ for symmetry. The haters, the fakers, and the goods.” He filled in three of the four boxes with the appropriate labels.

“The goods, then. You are suspicious of them?”

“You could say so. More incredulous, really, that such people exist. After all that has happened. But at least they are honest, like the haters.”

“They are as they appear.”

“Yes. Honesty is a simple virtue. But by far the largest group, and the most tiresome, are the fakers—the agents of smarm.”

“How can you identify them?”

“It’s easy. They use words like ‘amazing’ and ‘incredible,’ always in front of the largest possible audiences. They like to be seen complimenting people without giving reasons for these compliments. They want to get credit for distributing compliments, both from the subjects of these empty raves and from the wider community, though all parties see what they’re after.”

“Which is?”

“They are banking future compliments to be reflected back at them at the optimal moment. It’s all so much cloying social glue.”

“But that’s not new, this glue?”

“No, but this mutual pawing used to be tastefully hidden in the acknowledgements of unread books. Now it is out there for all to endure. Private praise is now worse than nothing. You approve of me? Say it where everyone can see. All this glue gums up the works, rendering it unusable. If it were subtracted, the online world would be one tenth its current size but twice as useful.”

“I see,” I said. “But you have omitted one type from your scheme.” I eyed the empty quadrant in the upper-right of his grid.

“ … “

Lou Reed’s Nephew looked confused.

“What about those who love people but pretend not to? Fakers, but in the other direction.”

“You mean ‘the curmudgeons?’” he said, tapping the empty cell. “The ones who love humanity so much they dare not show it, lest they expose their extra-tender, over-bursting hearts to the vagaries of contingency and chance.”

“Yes.”

“The ones whose outer crust of armor is fierce and … crusty in direct proportion to the softness and gooiness of the emotions housed inside this prickly carapace.”

“Yes.”

“The ones who hide behind wisecracks and shrewdness a sweetness that is impossibly rare.”

“Yes,” I said. Though I did not say so, I held out some hope that Lou Reed’s Nephew would, in the end, turn out to be of this most delicious and morally satisfying type.

“After careful study,” he said, “I have determined that this type has never existed outside romantic comedies produced in the final decades of the twentieth century. “But this doesn’t get at it fully,” he darted in another direction before I could react. “This is just the foundation.”

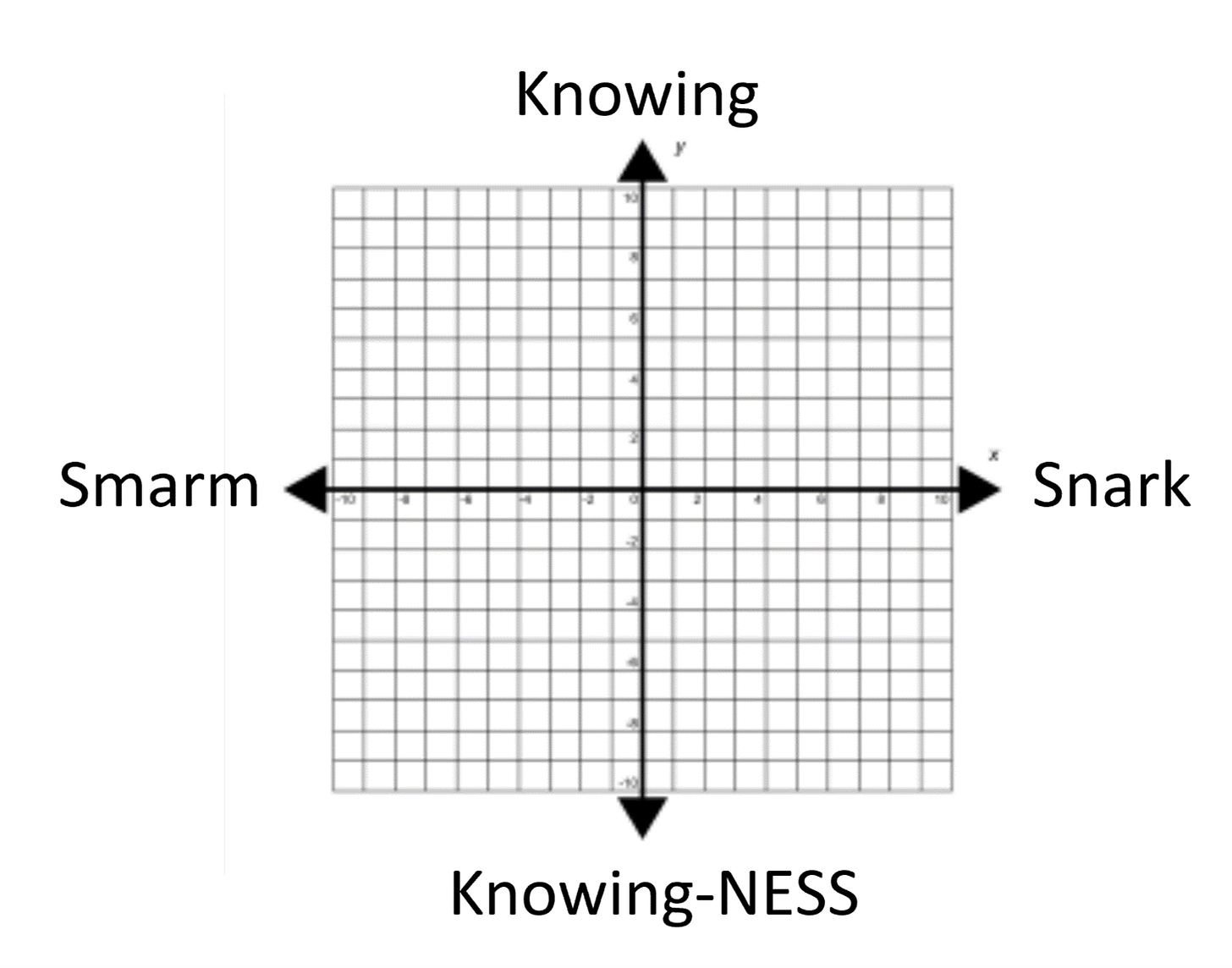

He erased the board and began again, this time with Cartesian axes. To these he added the poles under discussion—”Smarm” and “Snark”—at either side of the X-axis. Around these he stalked, from his cube and across the aisle into mine.

Back and forth.

Finally, he went back to the board and completed the remaining poles by scrawling the label “Knowing” at the positive terminus of the Y-axis and “Knowing-NESS” at the negative terminus.

“Snark and smarm have always been with us,” he said, gesturing toward the board. “But both can be performed either with knowing—actual knowledge—or with mere knowing-NESS.”

In his voice, as in his diagram, he landed hard on the -NESS. It sounded like the joy leaking from a band of cosplaying pirates.

“All civilized and advanced discourse, filtered—as it once was—for quality, has a certain knowingness about it, whether it was positive or negative, declinist or Whiggish. Snark and smarm are philosophical styles—attunements if you like—but knowingness is the medium itself.”

“You are exhausting,” I said.

“Enough of your indie rock nihilism,” he chided. “I’m almost there.”

He stabbed the board with useless black dots.

“But somewhere along the way,” he continued. “Knowingness and knowledge became decoupled. Knowingness became cheap to acquire, in oneself and others. There are children, all the time, growing up with knowingness in their veins, like you—with your shoegaze posturing.”

I didn’t know what to say so I said nothing.

“It became as common and unconscious as vocal fry, this ventriloquized knowingness devoid of knowledge, though even those who sought to buy it cheap and sell it high couldn’t believe their luck when they saw what happened next.”

“What happened next?” I asked, realizing the only way out was through.

“It turned out that no one could tell the difference. Those who mastered knowingness came to be revered as the knowing, and no one suspected the exchange. It was if all the gold bars in Fort Knox were replaced with painted logs without tripping a single alarm.”

“I am confused,” I yawned. “Nixon abandoned the gold standard. And at our first meeting, you professed to you know nothing, but now you seem to know an awful lot.”

“About this,” he admitted. “About this alone. I may be the world’s leading expert on feigning knowledge. My resume speaks for itself.”

“You don’t give yourself enough credit,” I said.

“No,” he said. “You give me too much. Everyone does.”

“Don’t you worry that on your deathbed you’ll regret the things you didn’t accomplish?” I asked.

“Why should I worry about that?” Lou Reed’s Nephew said. “I’m on my deathbed. It will be over before I know it.”