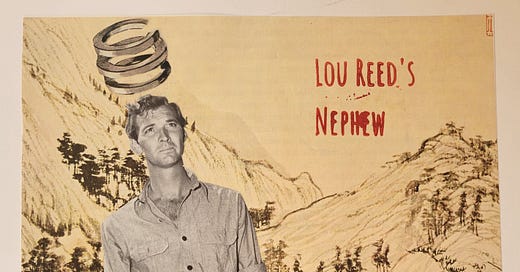

E16. Lou Reed’s Nephew on Gambling

He treated obscure knowledge as if it were common sense and common sense with suspicion.

“What do you know about gambling?” Lou Reed’s Nephew asked.

“Dangerously little,” I confessed. “I was once assaulted by a Teamster for fucking the deck from third base.”

“What’s that?”

“Fucking the deck?”

“No, a Teamster. Who doesn’t know not to fuck the deck from third base?”

“…”

“I didn’t have much experience either, though there was a game we played wagering on live rats when I was a kid,” he said.

“You grew up in Central Europe in the Middle Ages?” I asked.

“Rockville Centre in the 1990s. There was a church fair every weekend. The highlight of the summer was the St. Simon’s carnival. You knew it had started when you heard the cowbell they used to motivate the rats.

“The booth for the game, which didn’t have a name, was a big square. Each of its four sides was a bar-height ledge. You placed your bet by throwing a dollar on a number, like roulette. In the center there was a giant rotating wheel—laid flat—divided into slices, each corresponding to a number. In the center, the volunteers who ran the booth placed an enormous tame rat—there were two, so they could rest—and rang the cowbell until the rat scurried around and disappeared down a hole in one of the slices.”

“Sounds quaint yet barbaric.”

“It was. The entire scene was dangerous. You never knew when some bare-armed delinquent would try to start a fight. What are you looking at? he would say. If you said ‘nothing’ there was a fight. If you said ‘you,’ there was a fight. I’ve been suspicious of groups of men ever since.”

“Do they still play?” I asked.

“I went back last year. The booth was there, with the wheel and the slices, but the rats were gone—replaced by a single, pink rubber ball. The ball couldn’t hear it, but they still rang the bell with every spin.”

He stared into the middle distance, kidnapped by a thought.

“You were asking about gambling?”

“Right,” he said, freeing himself. “Apparently, I’m great at it. I just won the World Indian Poker Championship.”

He had been gone for a few days.

“How did you get involved with that?” I asked.

“Well, I was talking to my editor, and we were working our way through a list of poker tournaments. This was the first one that hadn’t already been assigned to somebody.”

“You have an editor?” This was the first I’d heard of this addition to his revenue mix.

“She admired my media criticism.”

“Exciting.”

“But Indian Poker. It’s a fascinating game.”

“I’m not sure I know it.”

“According to the official rules,” he said, reading from notes on his laptop. “One card is dealt face down to each player. Each player, without looking at his card, places it on his forehead so each player can see all cards but his own. There is a single round of betting and a show down.”

“Sounds like a ‘problematic’ game,” I said. “If you know what I mean.” I bounced my flattened palm against my lips in an “Indian whoop” any child would understand.

Lou Reed’s Nephew rolled his eyes.

“Don’t be so pious. Don’t you people claim to have invented grunge?”

“Sometimes,” I said.

“Nothing human is problematic to me,” he said. “The game is actually delightfully subversive. In regular poker, you are dealt cards and you keep them a secret from everyone else, but in Indian Poker you put your card on your forehead so that everyone else can see. It’s all inside out.”

“Topsy turvy.”

“Higgledy-piggledy.”

“And the cards are like Indian feathers. I get it. We still play this game in America?”

“It’s state by state. The tournament was in Arkansas.”

“My parents did play a version of this when I was a kid. That was gambling, too, even if it was a family game. They called it ‘Oklahoma Forehead.’”

“Red washing,” Lou Reed’s Nephew sniffed. “The behavioral economists who study it call it Single Panel Asymmetrical No-Peek, but where is the poetry in that?”

Every Saturday night, I remembered, my parents played cards with my aunt and uncle. I got to stay up late in the bedroom and watch TV, and I strained to overhear their conversations. There would be long, lingering breaks between hands. My mom and her sister would recount the details of their childhood, which had been lorded over by my grandmother, a house-coated boozer in the 1950s style. I overheard all the family secrets: the one about my great uncle who died, drunk, in a hotel room in Detroit. Another about an uncle who was stabbed by his uncle because of a woman. The one about another who loved to read and the ones about people who lived their whole lives together but never really loved each other. They seemed so far away, these stories, set in a time when everything was black and white and men wore hats, even as their lives spiraled out of control.

The games got more inappropriate as the night wore on. Mexican Sweat, Circle Jerk, Crazy Blind Man, Dirty Schulz, before arriving, finally, at Oklahoma Forehead. Then it would be time to go home, the inside of Dad’s Vega filled with the sweet smell of beer and mentholated cigarettes.

“My point is I knew it was almost time to go home when they got to Oklahoma Forehead, because it’s so silly,” I said.

“But that’s not because it’s silly. It’s because it’s so serious!” he exclaimed, surprising even himself. “It’s because it’s too serious,” he whispered, as if trying to erase his outburst.

“Okay.”

“Standard poker flatters us and stokes our illusions of mastery,” he said. I settled in for a lesson. “But Indian Poker is ego-destroying. You have nothing but your view of the other cards, while your card—your self—is possessed by others. People laugh, not because the game is silly, but because it is terrifying. Western poker attempts to master nature, but Indian Poker is raw, untamed nature. It is not for the weak.”

“And you are not the weak?”

“Apparently not. You should have seen the crack ups as the tournament wore on, people driven completely mad by the game. Early in the tournament, everyone folded in the presence of an Ace, of course. They knew that they could do no better than tie. Only later did I realize that the game was won, not objectively, but subjectively. I developed strategies for appearing unimpressed by Aces. I imagined my reactions to fours and applied them to Queens. I carefully ignored the player with the highest card, as if she were not a factor, though I was careful not to make this effort appear labored, which would have been a tell all its own.

“By the end of the first round, I became accustomed to the two phases of each hand, one cynical, the other desperate.

“As the cards were dealt, and each player fit them—as we had been instructed—into the regulation presentation trays held to our foreheads with nylon straps, my opponents’ eyes darted around the table. They tried to keep their reactions flat, so as not to give away any information. Then they would do a second sweep, in which they attempted various strategies. They might ignore a high card, or feign concern about a low one, or—if the game had gone on for some time—they might do the opposite, confident that other players would reverse the meaning of these glances.

“Having flooded the interpersonal zone with misleading cues, my opponents panned the chaos for clues about their own card. Their souls dilated, like eyes seeking light, with two possible outcomes. Finding a clue, they formed a clear idea of their card and bet accordingly. They detected something, or so they thought, which gave them an image of their card so vividly rendered that they could not imagine it otherwise, like when you are suddenly certain where you left your keys.

“Sometimes, however—particularly in the late rounds—they were unable to form even an erroneous belief about their card. After so many disappointments, they gave up, accepting that their theories were no more than wishful thinking. Finally, in extreme cases, they bet randomly, asked to be excused from the table, or simply broke down. Eventually, I could spot the exact moment when my opponents checked out, abandoned their illusions, and surrendered entirely to chance.

“I surrendered to chance long ago, so I had a leg up. I guess it’s no surprise that I won.”

“And you will now write about your triumph over these poor, weak souls?”

“Yes. That is the custom. But first I am doing a little research.”

“How little?”

“As little as possible.”

“What have you learned so far?”

“That Indian Poker was invented by Indians, Mr. Problematic. It is the Montezuma’s Revenge of the European mind.”

“Ew. And now you’ve appropriated it?”

“Stop, Professor Zinn!”

“Okay. How did this happen?”

“As you no doubt know, Pizarro, de Soto, and their horsemen seized control of the entire Incan empire in a bloodless coup at Cajamarca in 1532.”

I did not know this but was by now familiar with Lou Reed’s Nephew’s rhetorical method. He treated obscure knowledge as if it were common sense and common sense with suspicion.

“What you might have missed is that Pizarro’s feat was made possible, not by the backwardness, but by the sophistication of the Incan empire. It was centralized, like the kingdoms of Europe, with absolute power inhering in the body of one man, the Inca himself. Once he was seized, the kingdom was under the Spaniards’ complete control. His foreign captors taught the Inca to play chess, at which he excelled. They also taught him card games, which, like the wheel, had no analogues in Incan culture. But one day the Inca taught them a game.

“His servant dealt single cards face down in front of the Inca and his three Spanish guards, then picked up the one in front of the Inca and held it directly above the chief’s head. At first the guards took this to be a ceremony rather than a game. The servant, however, signaled for them to do the same, to hold their cards up in front of their heads. They complied. Once he surveyed them carefully, the Inca threw in a handful of the pebbles they’d been using in the games they had taught him. The soldiers looked at each other and snickered at the ridiculousness of it, before they, too, placed their bets. One folded. The other two stayed in. The Inca had a King.

“News spread quickly about the game, and how the Inca seemed to be exceptionally good at it. His lieutenants tried to explain it to Hernando de Soto, Pizarro’s second in command, but he couldn’t understand it, this inside-out game in which everyone revealed, rather than concealed, their positions. It was as if their horses had ridden them to Cajamarca and they had worn their skin outside of their armor.

“Pizarro dispatched de Soto to see the game firsthand. There were rumors that the Inca might have magical powers, so good was he at this game.

“De Soto entered the room where the Inca was held to find a game in full swing, the pebbles piling up in front of the imprisoned monarch as his three Spanish guards sat, cards pressed stupidly to their foreheads. De Soto took a seat directly behind the Inca. A strategic choice, chosen by a master strategist. He not only sat where the Inca could not see him; he could see what the Inca saw.

“After letting several hands pass in silence, he interrupted. He instructed one of the guards to switch seats with him so he could join the game. His first card came, and he removed one chain-mailed gauntlet so he could pluck it from the table and hold it to his forehead. He held it a little high, the other guards thought, but who were they to ask?

“With the first card, he immediately folded. With the next he wagered all his pebbles, as he did on the third hand. Within a half-dozen hands, de Soto had captured all the Inca’s pebbles. He stood up and ordered that the game never be played again.

“The Inca looked cowed and disappointed, and word spread quickly that it was perhaps de Soto who had magical powers.”

“So, he cheated.”

“Obviously. He could see his own card in the guard’s helmet. At the tournament they had to drape the entire ballroom in gauze to prevent this from happening, the temptation is so great.”

“But you found a way?”

“I couldn’t possibly comment,” he said. “You’ll have to read the article.”