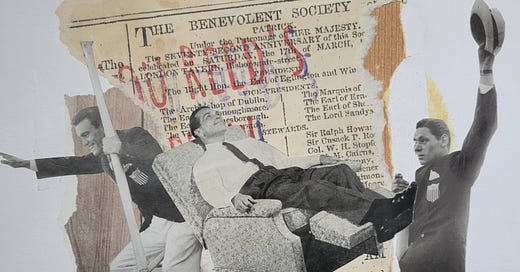

E27. Lou Reed’s Nephew on Narcissism

"The same perspective that tells you and me and everyone that we are the center of the universe also tells us that that isn’t true at all.”

“Do you think you’re the center of the universe?” Lou Reed’s Nephew asked.

“What a question,” I said. “You’re trying to pin the N-word on me, aren’t you?”

“…”

“Narcissist,” I clarified. I had noticed that people Lou Reed’s Nephew’s age were fluent in diagnoses, which they liberally applied to themselves and others.

Narcissist. Borderline. Anal.

“Not at all,” he said. “A narcissist is just someone who doesn’t think about you as much as you think they should. But you’re evading.”

I thought for a second.

“Yes, I do think I’m the center of the universe,” I said. “We all do. That’s our problem.”

“How can we all be the center if you’re the center?”

“From my point of view—the point of view that extends in front of my face—I’m the center of everything,” I said. “It starts with me and becomes vague and less real as it rolls away. But within that point of view, I come across other people. You, for example. People who I have no reason to believe don’t have the same perspective I have, but from a different position. They see like I see, but they see different things.”

“They see you.”

“They might see me. You see me, right? And what I gather from all this seeing is that now, at this moment, there are more than seven billion of us. The same perspective that tells you and me and everyone that we are the center of the universe also tells us that that isn’t true at all.”

“I see.”

“And it makes us all feel just a little uncomfortable.”

“You are uncomfortable?” Lou Reed’s Nephew asked.

“Aren’t you?”

“Not at the moment,” he said, shifting in his chair.

“I’m uncomfortable,” I said.

I stood up, crossed the aisle, and began drawing a diagram on the whiteboard in Lou Reed’s Nephew’s cube.

“It explains everything, really,” I said as I drew. “SoulCycle. The Khmer Rouge. In the end, you have to do away with either the self or the other to do something about this discomfort.”

The figure on the whiteboard looked like a giant burrito with two spider-like legs grasping, in opposite directions, for the ground.

“It’s like we’re sitting on a stool with two legs,” I said, tapping the whiteboard with his marker.

“That won’t stand,” he said.

“No, it won’t.” I said. “Uncomfortable?”